Learning Myths, Exaggeration & Hype

Feature Story – By Steven Just, Ed.D.

If cognitive psychology and its application to learning is a science, then there needs to be research evidence to back up our claims about which learning strategies work and which do not. Unfortunately, the profession of adult learning can be prone to myths, pseudo-myths, outright falsehoods, unjustified claims, hype and exaggeration.

In this article, we will examine some of these learning myths and subject them to scrutiny. Some of the claims we label as “myths” may be surprising.

Among the myths, pseudo-myths and exaggerated claims we will examine are:

-

The Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve.

- Dale’s Cone of Experience.

- The shrinking attention span of millennials.

- Visuals are processed 60,000 times faster than text.

The Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve

The Claim: Learners forget 80 percent or more of what they have learned within a month after a learning event.

The Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve is one of the best-known results in learning theory. The Curve demonstrates that what learners remember after an event drops steeply soon after completion of the event. (See Figure 1)

Ebbinghaus was a well-regarded German psychologist (1850 – 1909), and without a doubt he produced his forgetting curve in 1885. And we all know from personal experience that we rapidly forget much of what we have learned. So, what’s wrong with this claim?

It turns out that there are a number of factors that affect our ability to remember what we have learned. Among them are:

- Individual differences

- Prior knowledge

- Importance of the information

- Prior learning schema

- Repetition

- Retrieval

All of these factors contribute to learning retention. Depending on which factors are active, we actually have a series of forgetting curves, not a single, absolute curve. (See Figure 2)

Bottom Line: It is true that learners forget, but they do so at different rates, depending on the learning environment.

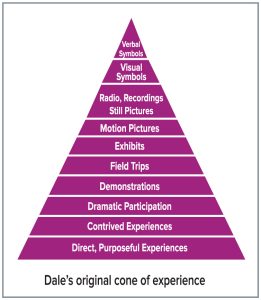

Dale’s Cone of Experience

The Claim: We remember 10 percent of what we hear, 50 percent of what we see and hear, and 90 percent of what we do. It’s widely believed, but is it true? The claim is based on Dale’s Cone of Experience, which we usually encounter in a form something like what’s show in Figure 3.

This myth is so plausible sounding that it is routinely taught as true in many education classes. To figure out what is going on, we need to go back to the source of the “research.”

Edgar Dale published his original Cone of Experience in 1946 (Figure 4). His purpose in developing the “Cone” was to create a taxonomy of learning methods from the abstract to the concrete, not to comment on learning retention. Also, Dale did not claim that each level of the hierarchy was preferable to the previous level. In fact, he argued that good instruction combines both abstract and concrete methods.

So, where did the retention numbers come from? It’s not exactly clear, but others have spent a lot of time researching when and where they were introduced (most likely sometime around 1970).

Bottom Line: The retention numbers are bogus, made up, without a shred of research evidence behind them.

Millennials Have the Attention Span of Goldfish

The Claim: Mobile devices have rewired the brains of Millennials so that they can no longer focus for more than eight seconds at a time.

If we are going to talk about attention span, we first need to define what it is. “Attention span” refers to the amount of time an individual can remain focused on a task without becoming distracted. Can most people, even Millennials, focus on a task for more than eight seconds? Certainly. It’s hard to keep any job if you can’t. And, everyone focuses for relatively long periods of time on an enjoyable movie, TV show, video, podcast, sporting event, video game, even a book!

Where did this erroneous statistic come from? It seems to have come from a 2015 Microsoft paper, though that paper never claims this was based on its own research.

Why is this erroneous number important? Because it is influencing how we develop content. There is good evidence that we disengage from learning after 8-10 minutes, hence the case for microlearning, but there is no evidence that we need to keep our learning nuggets under eight seconds!

The Bottom Line: It is true that we are more distracted than ever by our mobile devices, and this is a problem. But there is no evidence we can only focus for eight seconds at a time.

We Process Visual Information 60,000 Times Faster Than Text

We Process Visual Information 60,000 Times Faster Than Text

The Claim: We process visuals 60,000 times faster than text. This claim now seems to be everywhere. It has taken on a life of its own, kind of like “we only use 10 percent of our brains.” So, where did it come from?

Fortunately, Alan Levine has investigated this claim in detail and written a series of posts on his blog, “Cogdogblog.” He found that it seems to have arisen in an information brochure (not a research study) from 3M sometime in the 1980s, or maybe even earlier than that. It’s not clear. But in any event, it has been repeated so often that many just accept it.

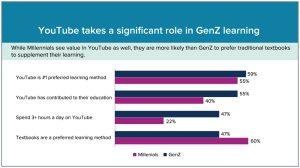

And it does have the patina of truth. We all know the expression, “a picture is worth a thousand words,” which is often incorrectly attributed to Confucius (yet another myth). We also know, anecdotally, that our learners enjoy learning from videos. A recent survey by Pearson revealed that Gen Z’s favorite learning platform is YouTube, and for millennials it’s a close second. (See Figure 5.)

Chair

Chair

What do we actually know about pictures and text? (Figure 6) We do know that people remember visuals better than text. This is known as the Picture Superiority Effect and it has been demonstrated in many studies. There is not 100 percent consensus on why, but one theory is that pictures are stored twice in the brain, once as an image code and once as a verbal code and are therefore easier to retrieve.

The Bottom Line: Like many learning myths there is a kernel of truth to this claim. Images are recalled better than words. But 60,000 time faster? Not likely. Probably not even 1,000.

Bonus Bottom Line: If you see a claim and the numbers are nice and round, chances are it is a myth or at least over-simplified marketing hype. Real research rarely delivers nice round results.

Dr. Steven Just is chief learning officer for Intela Learning. Email Steven at

sjust@intelalearning.com.

More Myths

Interested in more debunked learning myths? Look for additional articles on the Bonus Focus pages of the L-TEN.org website, www.L-TEN.org/BonusFocus. In future articles, Dr. Steven Just will address issues including:

- 70:20:10.

- Incidental music improves the learning experience.

- Learning objectives improve learning.

- You should create instruction to match someone’s learning style.

- Left brain vs. right brain thinkers.

- We use only 10 percent of our brains.

- It is possible to multitask.

- Brain training games improve cognitive performance.